Vznik Mozartova Památníku

THE PEOPLE OF PRAGUE PAY HOMAGE TO ME

2nd November - 26th November 2006

Mozart´s cult in Prague of the first half of the 19th century and the

Mozart´s Memorial in the Klementinum

The exhibition from the collections of the Music Department is organised

by the National Library of the Czech Republic

on the occasion of the

250th birthday anniversary of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

The event is held under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic as a part of the MOZART PRAGUE 2006 Project.

Mirror Chapel, daily except Mondays: 10:00 am - 6:00 pm

entrance fee 50,- CZK

Publication: The

People of Prague Pay Homage to me

|

The establishment of the Mozart

Memorial |

|

|

The Mozart Memorial was established upon the occasion of the Prague celebrations of the fiftieth anniversary of the first performance of Don Giovanni. The preparations clearly began as early as 1836, because the preparatory committee’s proclamation announcing the idea of establishing a permanent Mozart Memorial was Publisher in the Prager Zeitung in January the following year. The purpose of establishing this memorial was not only to create a collection of the Master’s works which would be permanently stored together with his bust at one of the Prague scientific institutions, but also to create a fund which would be used to finance both the memorial and the new foundation for conservatoire students and young talented composers. The founding members of the preparatory committee were the most significant personalities of the musical life in Prague at that time: Johann Ritter von Rittersberg, Jan Nepomuk Vitásek and Friedrich Dionys Weber. In order to raise the necessary funds, the preparatory committee held two public concerts. The first of them was held together with the Association of the Friends of Ecclesiastical Music in Bohemia (Verein der Kunstfreunde für Kirchenmusik in Böhmen) on 5th March 1837. As well as Mozart’s compositions, the program also included the cantata Mozarts Requiem which was composed by the Prague composer Robert Führer to words by von Rittersberg. Mozart’s works were also played at the second concert organised by the Conservatoire at the Wallenstein Palace on 9th April 1837. Both concerts were artistic successes and their takings were considerable. In April, the preparatory committee submitted an application for permission to establish the memorial to the governor and it received the approval on 27th July of the same year. A decision was also reached on the repository for the memorial, whereupon it was decided that it would be located at the Imperial and Royal Public and University Library in Prague. The preparatory committee was expanded to include the library’s director, Antonín Spirk, along with a number of other personalities from Prague’s cultural and political life and the newly constituted committee thus began working on the realisation of the memorial. |

|

|

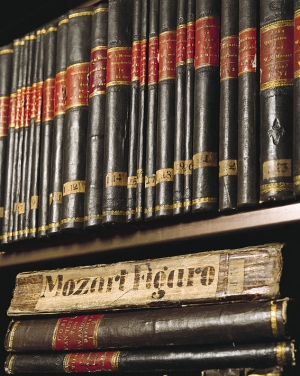

Apart from the Mozart bust made by the sculptor Emanuel Max, the main task was to acquire Mozart’s works. This they largely managed to do over a period of several months so that the Mozart Memorial was able to be ceremonially opened in the newly named Mozart Hall at the Klementinum on 18th September 1837. The sheet music was placed in two glass cases and the bust of Mozart was installed in the middle of the room. The Mozart celebrations in 1837 culminated with a gala performance of Don Giovanni at the Estates Theatre, during which von Rittersberg’s celebratory poem were also performed. The Mozart Memorial was also associated with a certain degree of dissension in musical circles. A similar project had also been established in Salzburg at around the same time (the predecessor of today’s Mozarteum) and the Prague initiative was seen to constitute a dissipation of the international strength required for this endeavour. Prague therefore had to make do with predominantly domestic resources, while Salzburg was able to draw on the collections throughout the entire German-speaking world. The idea of a monetary fund and a foundation therefore had to be abandoned, but the Mozart Memorial fulfilled its function. As is shown by the sheet music itself and by the memoirs of various contemporaries, the collection – which was unique in its day – has served generations of musicians and scientists.

The main section of the Mozart Memorial contains 181 compositions by W. A. Mozart, most of which are hand-written copies (117 works) with a lesser amount contained in period printed editions (64 works). This is admittedly a small amount in comparison with the numbers of works listed in Köchel’s thematic catalogue, but it is necessary to consider the fact that Mozart’s music was not as well known and accessible in 1837 as it is today. Most of the sheet music was acquired during the period from 1837 to 1838. The hand-written music was realised by a number of professional scribes, but older sheet music has also been exceptionally included in the collection. The printed editions mainly come from Leipzig or Vienna and they were often purchased from the Prague musical entrepreneur Marco Berra. Several rare autograph manuscripts and manuscripts were also acquired from Alois Fuchs, the well-known Viennese collector. Starting with Idomeneo, the Memorial contains all of Mozart’s completed dramatic works, with the exception of Zaide, which was unfortunately lost while von Rittersberg was still alive. Mozart’s early operas are missing, but this is understandable, because at the time of the establishment of the Memorial they were practically forgotten works and had long been unpublished. The same applies to a number of instrumental works, including symphonies, of which the Memorial has only the famous titles from the later years, but also the Italian symphonies from 1769–1771. Some of the works are even contained in the Memorial twice – this applies, for example, to Don Giovanni, but also to Idomeneo, despite the fact that it was never one of the repertoire works. The extensive representation of piano works, including 21 concertos, indicates which part of Mozart’s work was most widespread. Many of Mozart’s ecclesiastical works were also in intensive use more or less throughout the entire 19th century, but the numerous hand-written copies and arrangements meant that they were not an interesting commercial article for publishers. There were also various forgeries and disputed works. Apart from the famous Requiem, the Prague Memorial mainly contains Mozart’s masses, including, for example, the Messe in G, of which Mozart was certainly not the author. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the collection was supplemented (and concluded) with the purchase of collected edition of Mozart’s works published in Leipzig. However, the Mozart Memorial does not only include sheet music, but also librettos – both printed and handwritten – and a number of books. The Memorial also includes a bust of Mozart by the Prague sculptor E. Max, which is currently on display in the Chapel of Mirrors. The Memorial’s most valuable materials include four letters from Mozart’s family: one letter by Leopold Mozart, one by W. A. Mozart, a letter by Mozart’s mother and a draught letter by Constance, Mozart’s wife. Of interest are also the presumed autograph manuscripts of Mozart’s works (a set of dances and marches, practise exercises and one draft) and an autograph manuscript of a small piano work by Franz Xaver Mozart, the composer’s youngest son.

Mozart’s three visits to Prague (if we do not count his short stopovers on journeys in 1789) did not give rise to many compositions, but for all that those which he did write here were artistically unique. It is understandable that the Memorial has dedicated special attention to these works and that there are therefore several such specimens in the collection. Mozart’s first stay in Prague occurred in January 1787 thanks to an invitation from the members of the theatre orchestra and the ”society of great music connoisseurs” as Leopold Mozart wrote in a letter to his daughter. Mozart became acquainted with Prague audiences and with the local musical circles, he performed at a concert as a pianist with enormous success, he presented his new D major symphony (which became known as the ”Prague” symphony), he conducted a performance of Figaro and he composed a series of so-called German dances apparently for Count Pachta. His second stay in the autumn of 1787 was the most artistically fruitful of them all. Mozart completed Don Giovanni here in a friendly atmosphere, the score of which hides varied references to the first performers. The exceptional concept for this opera which reflects the artistic freedom which he found here is also associated with Prague. Just a few days after the premiere, he composed the large concert scene entitled Bella mia fiamma, addio for his long-time friend, the soprano Josepha Duschek. Before leaving, he also wrote two small songs: Es war einmal, ihr Leutchen and Das Traumbild. Mozart’s last visit was less happy. At the turn of August and September 1791, the composer completed La clemenza di Tito here with the help of Franz Xaver Süssmayer. This opera was written for the coronation of Leopold II and it was once again popular with the people of Prague, but it was not well received in court circles. His last Prague work is possibly the bass aria Io ti lascio o cara – a kind of emblematic leave-taking which the Prague cult again associated with the figure of Josepha Duschek. Don Giovanni and Josepha Duschek stand at the centre of the Prague Mozart legends, but they are also the basis for the local Mozart tradition. Both names are also in some ways symbols of Mozart’s magnificent success and at the same time of the most joyous periods in his short life.

From the end of the 18th century, Mozart’s music was performed in various forms on theatre and concert stages, in churches, in the streets and in households. It is relatively easiest for us to follow the fate of his music at the Estates Theatre. Mozart’s works were very often included in the repertoire for as long the theatre was hired by Domenico Guradasoni (1731–1806). 1794 was definitely Mozart’s year – all of his operas from The Marriage of Figaro through to The Magic Flute (as Il flauto magico) were performed in Italian at the Estates Theatre, while there were also three German titles and The Magic Flute in Czech. After Guardasoni’s death, the Italian company had to give up the stage to the ”national” German language theatre. However, Mozart still belonged among the most played authors, including operatic performances in Czech which were renewed in 1824. Don Juan (i.e. Don Giovanni) was performed in 1825 and this was soon followed by The Magic Flute and Cosi fan tutte. Even though these performances were not overly numerous, they stood at the birth of the Czech operatic tradition and the translations of Mozart’s librettos assisted in the search for a path to Czech operatic poeticism. However, not even the strong Prague cult and the regular celebrations could prevent the process of the adaptation of the composer’s works to the needs of the performers and the changing tastes of the day. Not even Don Giovanni, perhaps the most sacrosanct of Mozart’s Prague works, escaped this process and it was performed at the Estates Theatre in adaptations with spoken dialogue instead of the recitatives, with added scenes and characters and in both German and Czech productions. The otherwise conscientious and Mozart-honouring Carl Maria von Weber also adapted to this trend when he conducted the Prague Opera from 1813 to 1816. A positive exception were the special performances prepared by Giovanni Battista Gordigiani, the professor of singing at the Prague Conservatoire, who returned to the original Mozart partituras, including the recitatives, in the 1840s. A further important institution which regularly performed Mozart’s works was the Prague Conservatoire which commenced its activities in 1811. In the first decades of its existence, Mozart’s works constituted approximately 60% of the repertoire at the school’s concerts. This number later fell, but the Mozart tradition at Conservatoire remained in place for a long time. The Mozart cult was secured at the Conservatoire by its first principal, F. D. Weber, but also by other members of the teaching staff. The Prague Conservatoire Orchestra and the Estates Theatre Orchestra were for a long time the only ensembles which regularly performed Mozart’s more expansive works. The orchestra of the Verein der Kunstfreunde für Kirchenmusik in Böhmen was also involved in this to a lesser extent, but it mainly performed oratorios or cantatas. Apart from some Mozart symphonies, it usually played the oratorio Davide penitente and the Requiem. In 1841, Prague acquired a further institution with concert activities. It was the Žofín Academy, a private music school which was mainly oriented towards the training of singers. For this reason, the repertoire at its concerts frequently included vocal works, but there were also regular concerts of instrumental chamber works. Mozart was most played there in the second half of the 1840s when the Academy was led by Jan Nepomuk Škroup, who also prepared a gala concert in 1846 in memory of the death of Mozart. The most eloquent testimony is given by the sheet music itself. The hundreds and up to thousands of preserved pieces of sheet music, both hand-written and printed, were regularly used, not only during the public performances of virtuosos, but also in musical salons and households by more or less all levels of society. Alongside the original Mozart works, there were also numerous arrangements of Mozart’s larger works – especially transcriptions of operas and symphonies for piano or for wind and string ensembles (quartets, quintets and so on). Throughout the entire 19th century, church choirs (and not only in Prague) were richly supplied not only with Mozart’s masses, but also with various arrangements of his operatic arias or ensembles, some of which were rather surprising. Prague also contributed to the dissemination of Mozart’s works in the area of musical publishing, albeit only to a modest extent. The traditions in this field were weak in Prague; enormous amounts of sheet music were disseminated by means of hand copying and so the first specialised company in Prague was that of the Italian settler Marco Berra (1811), who (just like J. Hoffmann and others later) was unable to compete with the Leipzig and Viennese publishers. However, an overview of the Prague production offers a number of interesting pieces of in formation – whether it was the unique printing of Josef Wenzel or the bibliophilic edition of Mozart’s popular song Das Veilchen (The Violet).

The esteem for Mozart in no way ended with the performance of musical works. The news of the artist’s unexpected death on 5th December 1791 soon reached Prague where it gave rise to great emotion. It opened up new sources of feeling and the esteem for Mozart was strengthened by noble anguish and reverence. This contributed to the perception of Mozart as a completely exceptional being, but also to his ”appropriation”. The veneration of the Mozart Memorial in the following years became an obvious obligation for Prague. The requiem mass organised by Josef Strobach, the leader of the theatre orchestra, became an exceptional celebration. This was followed by several academies in support of Mozart’s widow and orphans and a generous act on the part of František Xaver Němeček, who took over the upbringing of Karl Mozart, the composer’s eldest son, from 1792 to 1797. It was also Němeček, at that time a highly influential critic, who published the first Mozart monograph in Prague in 1798. All of these events reinforced the Mozart cult, but it also drew strength from elsewhere. The desire for ”national” art – both German and Czech – also played a role. Throughout the entire first half of the 19th century, Mozart was therefore esteemed as a representative of German art and he was established as the antithesis of the Viennese singspiel and the new Italian opera led by Rossini. Mozartism was clearly also part of the rivalry of some Prague musical ”parties” in the first decades of the 19th century. The opinions of musical art were further polarised by the music of Ludwig van Beethoven and later also by that of Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Robert Schumann. Prague musical greats such as F. D. Weber or V. J. Tomášek propagated the Mozart tradition, but not as dogmatically as it later seemed. However, part of the musical public undoubtedly saw in Mozart the acme of musical development and they had difficulty in accepting the new romantic movement. It is nowadays difficult to estimate to what degree the Mozart cult was also active in this.

As the period in which Mozart was accurately remembered passed, the creation of legends increased and these have been mostly preserved to the present day. The real basis for Mozart’s relationship with Prague was coloured and developed. Sentences such as ”the people of Prague understand me” and ”the Czechs recognised me in every work” therefore received the flavour of misused statements, both in Czech and German speaking circles. The year 1856 can be seen as a certain landmark in the Mozart tradition. The January celebrations of the one hundred year anniversary of Mozart’s birthday in the form of several concertos and church services were truly an exceptional cultural event. Almost all of the musical institutions and tens of artists joined forces and there were speeches and celebratory poems, folk celebrations and even artistic rivalries and gibes from some critics. Czech readers were then treated to a sensational discovery – Mozart’s Requiem had been secretly commissioned by none other than the ”Czech Count von Wallenstein”, which meant that Czechs could lay claim to this work, because ”it was written at the commission of a Czech aristocrat for a Czech family.” The poem of Josef J. Kolár which was recited at the main concert on 27th January at the Estates Theatre also reflected this exalted nationalistic spirit. A young Bedřich Smetana also performed at the concert in Mozart’s famous D minor piano concerto (KV 466), for which he had composed his own cadenzas. August Wilhelm Ambros, one of the founders of modern musical historiography and at that time a professor at the Prague Conservatoire and a music critic, appreciated Smetana’s stylistic playing which was free of external virtuosity and constituted a return to Mozart’s original. His later evaluation of the Prague Mozart cult was, however, highly critical and he significantly contributed to the negative perception of this cult by later generations. However, Ambros’ contemporary, Smetana, came to grips with Mozart’s legacy in completely different way. In 1843, he wrote in his diary in German: ”I am a tool of a higher power. With the help and grace of God, I will be on a par with Liszt in technique and with Mozart in composition.” and he lived up to this credo in a remarkable way. The great celebrations of 1856 can be perceived to a significant extent to constitute the symbolic closure of one epoch, in which a generation of artists and students actively came to terms with Mozart’s legacy and at the same time with the romantic art which was assuming its form. |

|

|

The Mozart Memorial and the

Clementinum today |

|

|

The Mozart Memorial and the Mozart tradition at the Klementinum is not merely a piously commemorative monument, but on the contrary it is a living legacy. Mozart constitutes one of the priorities of the Music Department’s strategy for the formation of its collections and the Music Department also contributes to Mozart research within the framework of its (modest) possibilities. The Mozart Memorial and other historical Mozartiana is used by the international research community and it has repeatedly been used in critical publications of Mozart’s works and to increase the accuracy of the catalogue of his works (KV = Köchel-Verzeichnis). The Music Catalogue at the National Library’s Music Department, which contains information about all of the most important musical collections within the republic and where sufficient attention has been paid to the Mozart sources, is also of great international significance. In this final section, we will therefore mention some of the various types of Mozart projects – catalogues, editions and monographs – which form a permanent bridge between Mozart and those who are interested in his works in every period. At the beginning of 1784, Mozart established his own catalogue of his works and he maintained it up to his death. This valuable source provides not only unique specific information, but also a view into the composer’s thoughts, because the list does not include some (mainly unfinished) works and we can but speculate whether Mozart simply forgot to enter them or whether this was intentional. However, Köchel’s monumental thematic catalogue (arranged chronologically), which at the time of its establishment was a model scientific work and is still used today after several fundamental reviews, towers above all other catalogues. Like Köchel’s catalogue, some Mozart editions led by the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe also have a paradigmatic significance for editing practise. The main part of the so-called old collected edition of Mozart’s works (die Alte Mozart-Ausgabe) was published in 1877–1883. |

|

|

The Neue Mozart-Ausgabe dates from 1954 and it is a model example of a modern collected edition designed for both science and musical practise and based on critical editing work and widespread research into the sources. However, we can also follow the problem area of editing in association with the Mozart sources at the National Library headed by the Memorial. A number of the pieces of sheet music stored here have been used as an important comparative source or directly as the main original for various editions. While musicians have the greatest need of high quality sheet music editions, the greater public is mostly interested in biographies of Mozart. Otto Jahn was one of the most significant Mozart biographers and his four-volume Mozart (Leipzig 1856–1859) continues to be relevant for those with a serious interest in the composer and the width of its scope makes it an unsurpassed book (it was later reworked by Hermann Abert, Leipzig 1920). Other great Mozart biographers included Alfred Einstein or the Frenchmen Théodor de Wyzewa and George de Saint-Foix. The most important Mozart biographies prior to Jahn mainly included the book by the Danish diplomat George Nikolaus Nissen, who married Mozart’s widow, Constance, in 1809 and dedicated the rest of his life to caring for the legacy of her first husband. However, the book Leben des k. k. Kapellmeisters Wolfgang Gottlieb Mozart by Mozart’s Prague friend and admirer František Xaver Němeček, which was published in Prague in 1798, stands at the very beginning of the extremely long series of Mozart biographies. For Czech admirers, Mozart’s art constitutes a permanent inspiration and challenge. |

|